And how Drake’s diss track ties into it all

This essay and all new writing is also published in my newsletter which you can sign up for here.

Throughout history, artists have consistently experimented with and pushed the boundaries of what is possible with new technologies in ways that further society’s collective understanding of a technology’s capabilities and use cases. The tinkering of early animators like John Whitney laid the groundwork for the computer graphics and animation industry. More recently, artists like Holly Herndon have experimented with the use of AI voice cloning to allow anyone to generate music with an artist’s voice prompting the public to critically consider artist likeness and content provenance in a world where AI tools can cheaply generate content in the likeness of any artist. Herndon’s work felt particularly prescient earlier this month as a new Drake song sent hip hop communities into a frenzy with its use of AI voice cloning.

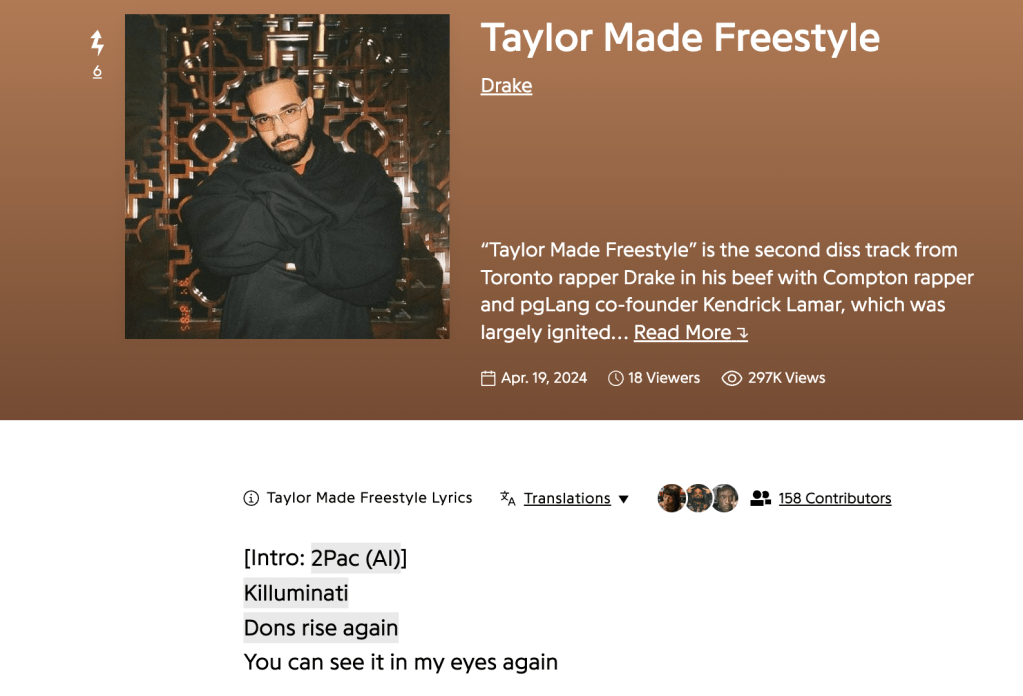

Taylor Made Freestyle

Drake and Kendrick Lamar have been slinging disses back and forth in their recent releases and Taylor Made Freestyle is Drake’s latest response.

The most controversial aspect of the track was the use of AI voice cloning to incorporate verses from Tupac and Snoop Dogg with the bulk of the criticism centering around what was suspected to be unauthorized use of the deceased Tupac’s likeness – the track begins with Tupac’s voice rapping a verse goading Kendrick to respond. A week later, these suspicions were confirmed with Tupac’s estate filing a cease and desist against Drake to take down the track.

Drake is intimately familiar with AI generated content having been voice cloned on a viral TikTok track Heart on My Sleeve last spring. The notable difference this time is that he, with his widely recognizable brand and access to broad distribution, is the one certifying a track that prominently uses AI generated content. While it can be argued that the creation of Heart on My Sleeve likely involved a mix of AI generation and non-trivial human effort, it was easier for the public to simply categorize the track as AI generated in the absence of a prominent human with a known brand to anchor to. With Taylor Made Freestyle, not only is the mix of AI generation and non-trivial human effort more recognizable when listening to the track (Drake himself raps one of the verses), but the face of the track is also that of one of biggest music artists in the world. In this case, should we be categorizing the track as AI generated if two out of three of the verses were created using AI? Is a binary categorization of content as AI generated vs. human generated even useful here?

AI generated samples everywhere

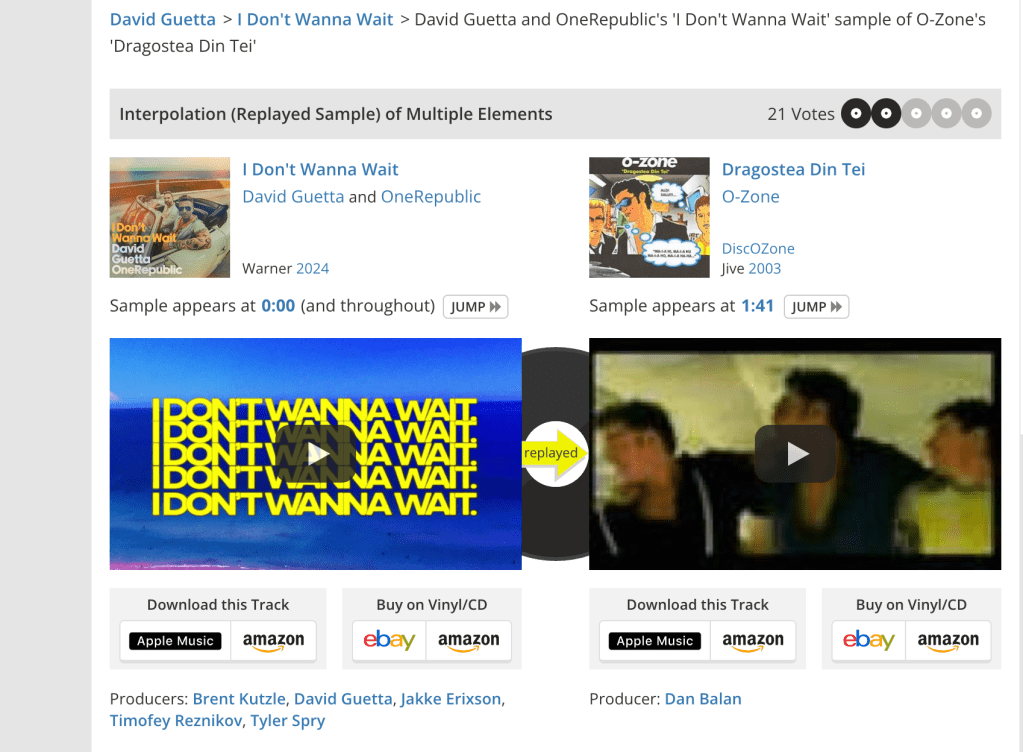

The story of the music industry, and the hip hop genre in particular, is a story of sampling – the process of incorporating parts of existing songs into new songs. It only takes a few minutes of browsing on WhoSampled to see how much new music is built on a composition and remix of past music. Samples are everywhere!

Taylor Made Freestyle shows how sampling could evolve in a world of generative AI. Instead of incorporating samples from fixed source music, the track incorporates samples dynamically generated by AI in the style and likeness of specific artists. The use of AI in the sample generation process can be viewed as the next evolution of audio filters and edits applied in a production studio. Artists started off by playing with reverb and distortion, then they dabbled with autotune to alter pitch, and now they are using generative AI to manipulate timbre to convert any sound into their instrument and voice of choice. The first verse of Taylor Made might be rapped by AI Tupac, but converting the verse to use Drake’s voice is just a tweak away in the studio.

If AI generated samples are the next evolution of sampling, we can expect a large portion of songs in the future to contain AI generated samples. Nate Raw compares this future of music with the ChatGPT-ification of text on the Internet – just as traces of ChatGPT can already be found in everything from press releases to blog posts (drink for every instance of “delve” that you see online today), traces of AI will be found in everything from hip hop diss tracks to EDM festival anthems.

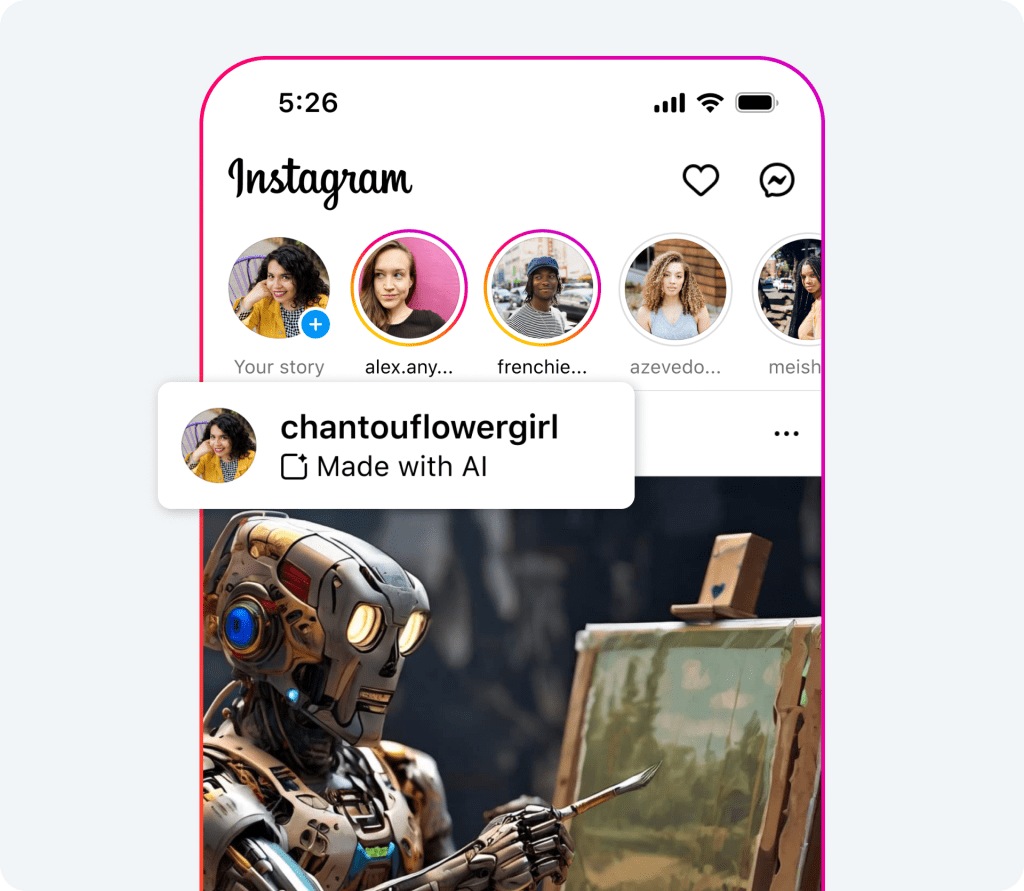

Made with AI labels

The likely proliferation of AI generated samples should be kept in mind when considering Meta’s plans to start adding “Made with AI” labels on its platforms (i.e. Facebook, Instagram, Threads) starting in May.

The rollout of Made with AI labels is largely motivated by pressure to establish defensive measures against misinformation driven by photorealistic AI deepfakes during the 2024 election season. The system is likely to undergo plenty of iteration over time, but as-is it already highlights some of the challenges in deploying defensive measures against negative uses of generative AI without stymieing experimentation with positive uses.

Does “Made with AI” mean that the content was entirely generated using AI? Or does it mean that the content includes some AI generated portions? If the intent is for the label to convey latter, will consumers interpret the label in that manner or will they still interpret the label as the former? This last question is particularly important because there is clearly a difference in an image generated via Midjourney and that same image used as a canvas for an artist to overlay additional aesthetic edits with other tools. Similarly, there is also clearly a difference between a purely AI generated song from Suno vs. a song that is the composition of AI generated samples and human generated sounds. All of these examples can be categorized as content with AI generated portions. But, if all of these examples are labeled as “Made with AI” and consumers end up interpreting the label as an indication that the content was entirely generated using AI then artists that incorporate AI in a larger creative process would be lumped in with a sea of other commoditized AI outputs in the eyes of the consumer. Furthermore, a “Made with AI” label will lose utility as traces of AI make their way into the majority of content – the label probably won’t be very useful if most content has it.

All that said, another Meta press release hints at a future direction that could be more productive:

While the industry works towards this capability, we’re adding a feature for people to disclose when they share AI-generated video or audio so we can add a label to it. We’ll require people to use this disclosure and label tool when they post organic content with a photorealistic video or realistic-sounding audio that was digitally created or altered, and we may apply penalties if they fail to do so.

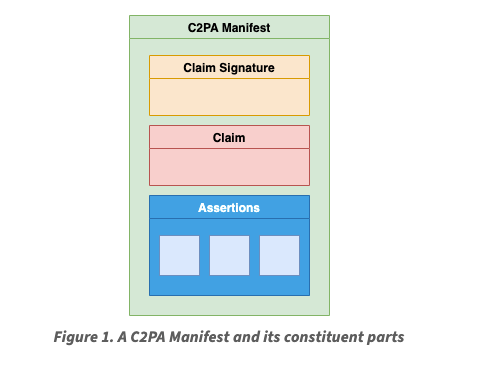

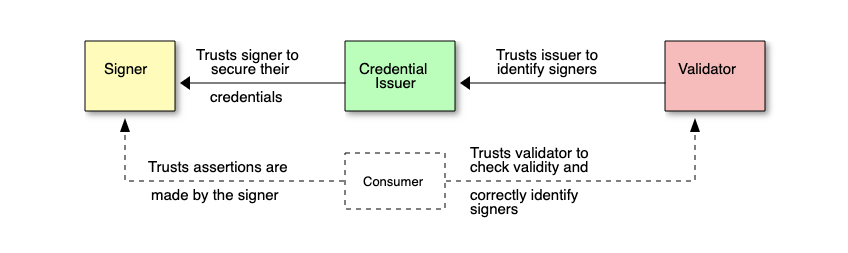

Setting aside the contents of the label for a moment, the most interesting aspect of this approach is that it would create an incentive for creators to make transparent assertions about the provenance of their content and only applies penalties if those assertions are found to be false. The use of AI is certainly an important assertion to include, but ultimately what is most important is to ensure consumers have sufficient context based on content provenance. This context can help mitigate misinformation if the consumer, as an example, knows that the content originated from a camera at a specific time and place and not an AI image generation tool. This context could also help content using AI generated samples stand out in a sea of commoditized AI outputs if the consumer, as an example, knows that the content originated from a novel workflow that combines AI and human efforts.

There are plenty of open questions and challenges here. Can the friction involved in making these assertions be reduced and automated? Is there a UI that can surface this information in a way that meaningfully influences consumer behavior? Meta suggested penalizing inaccurate assertions of provenance – is it possible to also create an ecosystem that rewards accurate assertions of provenance from both the creator and others? But, relative to the binary categorization of content as AI generated vs. human generated which feels too reductive and constraining, this seems to be a more promising direction to explore for fostering a dynamic ecosystem of creative content while minimizing the harm of AI powered misinformation.